The Greatest Test Match Ever Played Explained for Non-Cricket Fans

Since discovering cricket a few years ago, the biggest drag has been the inability to explain some of the game's most memorable moments and achievements to folks not familiar with the sport. It's easy enough to show a YouTube clip of a great catch or a great throw, but how do you explain what Ben Stokes did at Headingley in 2019 or what Cheteshwar Pujara did against Australia in 2021 to someone who doesn't understand the game? I was willing to live with and accept that disconnect between cricket fans and non-fans…until now.

The second New Zealand - England Test was one of the most amazing sporting events I've ever witnessed. It was a rollercoaster for five days and became a beyond-intense nailbiter as it reached its conclusion. As my current life's goal is to introduce cricket to American sports fans, it would be negligent on my part to not try to explain what happened over the past few days in Wellington, New Zealand. So here it goes: the greatest Test match ever played explained for folks who may not know a lot about cricket.

A bit of backstory: New Zealand is the defending World Test Championship winner and currently ranked number five in the world. England, after years of being a subpar Test team, are now ranked number three in the world after adopting a more aggressive batting approach and running off a series of Test wins. (And Test is always capitalized.) This was the second Test in a two-Test series. Visiting England had already won the first one pretty easily after New Zealand's batting collapsed late in the match. England went into the second Test looking to sweep the series.

Batting lineups in cricket are pretty similar to lineups in baseball. (A lot about cricket is very similar to baseball.) Generally, speedy guys who can spray the ball and keep fielders on their toes are your top of the order hitters. You have your more classical hitters at four, five, and six. And then you have the rest of the team -- primarily weaker hitters and bowlers (pitchers) -- rounding out spots seven through eleven. Each team's at-bat (or innings, which is always plural) involves every player batting once. Once a batter is out, he's done for the rest of his team's at-bat. And that can be after scoring 3 runs or 350 runs. The ways that someone is out or "loses a wicket" are also very much like baseball. There are fly outs. There are plays that are very similar to ground outs. And there are plays that are very similar to strike outs.

For Test cricket, the goal is to have the early and middle-order batters put up the bulk of your runs because, well, that's their job. Scoring runs is similar to baseball. Depending on the baserunning, a hit can either be a single (one run), a double (two runs), or a triple (three runs). If a hit ball leaves the field on a bounce -- like a ground rule double -- it's four runs. And if it leaves the field on the fly -- like a home run -- it's six runs. That said, England lost three wickets in their first at-bat incredibly early. Basically, they had lost three of their big guns and had only 21 runs to show for it. A typical at-bat for a team in Test cricket usually puts up around 300 runs, so you generally want to be in triple-digits before losing three batters. In boxing terms, England came out for the first round and walked right into a massive blow to the jaw. New Zealand could have pretty much locked up the five-day event right there if they had been able to keep the foot on the gas and take out a few more of England's hitters.

Enter Harry Brook. Brook is a 24-year-old rookie who had shown promise before being brought up to the national team, but has been an elite batter since making his debut. In eight at-bats before this Test, he had an average of close to 80 runs per at-bat and had scored 100 runs or more in three of those eight at-bats. (Scoring 100 runs -- often called a "century" -- is sort of the equivalent of getting four hits in a game or hitting three home runs in a game in baseball.) For perspective, the current top-ranked Test batter in the world, Australia's Marnus Labuschagne, has an average of 57.4 and has scored 100 in 10 of 60 at-bats.) England needed him to come in and stop the bleeding. And he did. Before he was done, he had scored 186 runs and England had picked itself off the canvas and had rebounded from a horrible start to finish its first at-bat with a very strong 435.

New Zealand started their first at-bat just as poorly as England did and quickly found themselves at the exact same and miserable score of 21 runs with three wickets down. But unlike England, New Zealand couldn't get things back on track and they limped to an unimpressive 209 before recording their tenth and final out.

Here's where things started to get interesting. In Test cricket, each team bats twice. Team A bats, then Team B, then Team A again, and then, finally, Team B. Here, though, since England's lead was so big, they had the option of having New Zealand go right into their second at-bat. The idea being that they would hopefully be able to get them out again just as easily, win the Test, and everyone could go home by the end of the third day. Unfortunately for them, that's not what New Zealand had in mind. New Zealand batters completely blocked out their lackluster first at-bat and went to town in their second at-bat.

Test cricket is a grind -- both physically and mentally. It's like playing a double-header -- old school with nine-inning games -- for five consecutive days. Each day has about six-and-a-half hours of play. And the final score is cumulative -- meaning there's no room for any let up during any of that time. As New Zealand passed the 300 mark and then the 400 mark, England's worst nightmare was beginning to take shape. Their bowlers, who had no trouble with New Zealand in their first at-bat were now getting tired. Really tired. As a result, instead of relying on their usual core group of four of five bowlers, players who don't usually bowl were brought in to give the primary bowlers a break in hopes that their arms would grow back.

And "bowling" is a misleading term. The bowling motion is slightly different from a pitching motion in baseball, but the top guys can still get the ball into the 90s. It's an intense, explosive action and probably not the kind of thing you want to be doing for two-and-a-half straight days. By the time New Zealand was retired after scoring 483 runs, England had bowled from about midway through play on Day Two until almost the end of play on Day Four. All told, it was over 1300 balls bowled. Over the course of two and a half days, Stuart Broad -- who can hit speeds close to 90 mph -- bowled 230 balls. By comparison, that's about two week's worth of real-game deliveries for a baseball pitcher who's on a five-day rotation and a 60- or 70-ball pitch count. Despite this, England opened their final at-bat needing a very reachable 256 runs to secure the victory.

Test cricket is played in "business hours" -- 10:00 am to roughly 5:30 pm depending on light. Folks in New Zealand tuned in for the final day with England hoping to score a final 210 runs but having already lost one wicket at the end of play on Day Four. Folks hoping to watch in England would have to be drinking lots of tea or else be vampires because the majority of the action would take place well after midnight. For folks in the US, though, the timing was perfect. Play went from 5:00 pm until about 12:00 am every day on the east coast. And because it was carried by ESPN+, almost 25 million people in this country had the chance to watch the match on a service that they were already paying for.

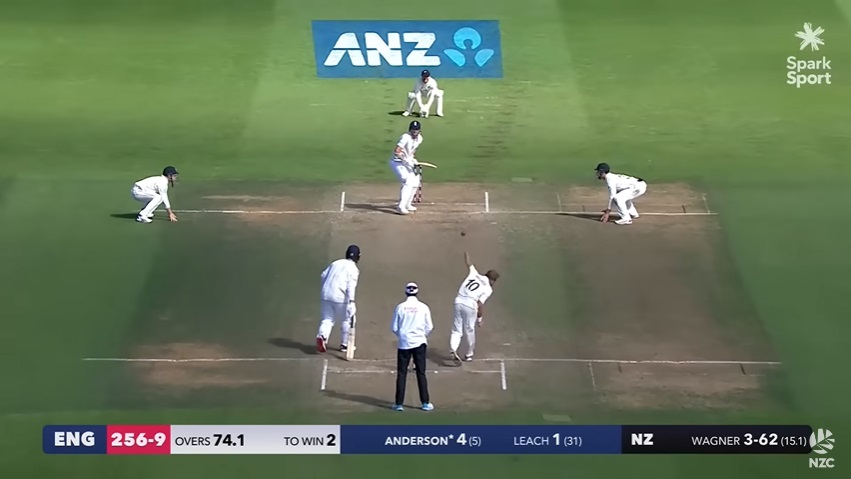

But New Zealand wouldn't make the last 210 runs easy for England. Four more outs happened quickly -- including phenom Harry Brook being out on a baserunning snafu before scoring a single run -- and England found themselves still needing 176 runs with half their outs gone -- and most of their big hitters done for the day. Momentum began to swing back to England's side after they crossed the 200 mark without losing another wicket. They now needed just 58 and they still had five outs left. But like the heavyweight slugfest this was, New Zealand responded with three more quick outs and the Brits were down to their final two outs while still needing 43. England plodded back and brought the Kiwis to the brink of defeat as they reduced the deficit to seven with two outs still remaining. A deep fly out cost them one of those outs, but clutch hitting from bowlers not known for hitting brought the game to the edge. England needed only two runs to win with one out remaining.

So now the match could end on any ball and it could go either way. But it was bigger than that. Not only was this an international event, it was one of the greatest Test matches of all-time. One of the guys in the center of the field -- either the bowler or the batter -- is going be a national hero. One of them will go down in history as either the guy that got the final wicket or the guy that drove in the final runs. The other guy? Probably not as much. Thirty-six year-old Neil Wagner got England's James Anderson to chase a ball and tip it to one of the New Zealand fielders. The match was over -- the greatest Test match I've ever seen -- and New Zealand became only the second team in cricket history to win a Test match by a single run.

Hope you understood all that. If that whet your appetite for more cricket, check out the rest of the CricAmerica site.

© CricAmerica.com/Steve Steinberg 2023